It’s not just individual patients who are in the dark… Employers are in the dark. Governments are in the dark. It’s just astonishing how deeply ignorant we are about these prices. Martin Gaynor

Summary

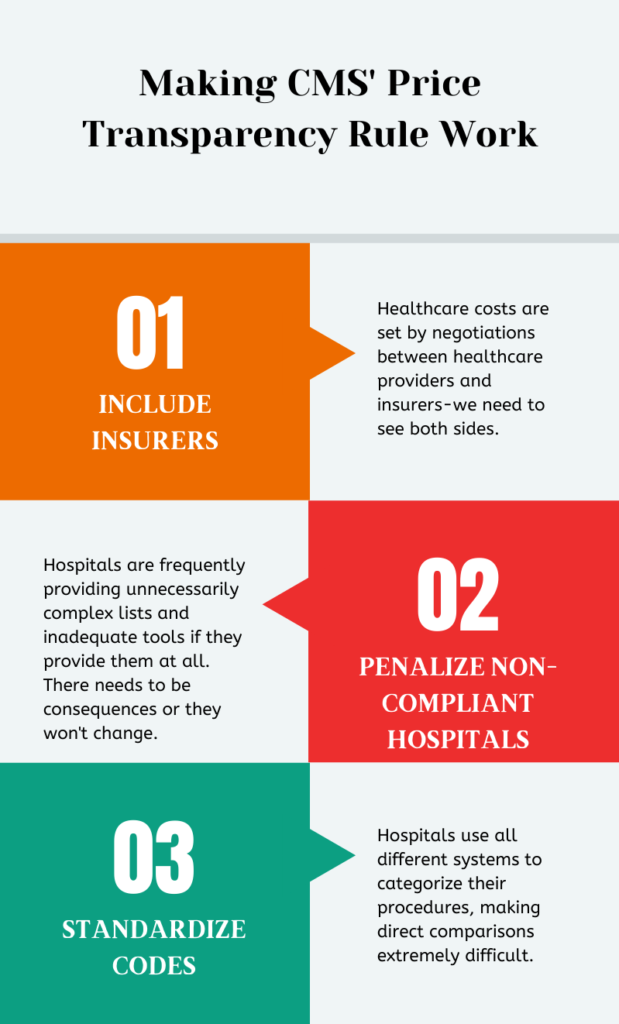

A year after its implementation, the government’s price transparency regulation is failing. The government requirement that hospitals begin disclosing their prices is not helping patients. With no meaningful penalties for non-compliance, and no standardization as part of the regulation, hospitals are reporting the prices in wildly different ways, if at all. Moreover, the industry preference for consumer price tools are woefully inadequate even when they “work,” as hospitals do not report estimates within any kind of reasonable range.- The government and hospitals could both improve it. Health prices are complex because of unique features of our market-based healthcare system, but the price transparency regulation would be significantly improved with three key changes: requiring insurers to begin disclosing reimbursement data, instituting significant penalties for hospitals and insurers who fail to comply, and requiring both a set coding system and plain language descriptions of procedures.

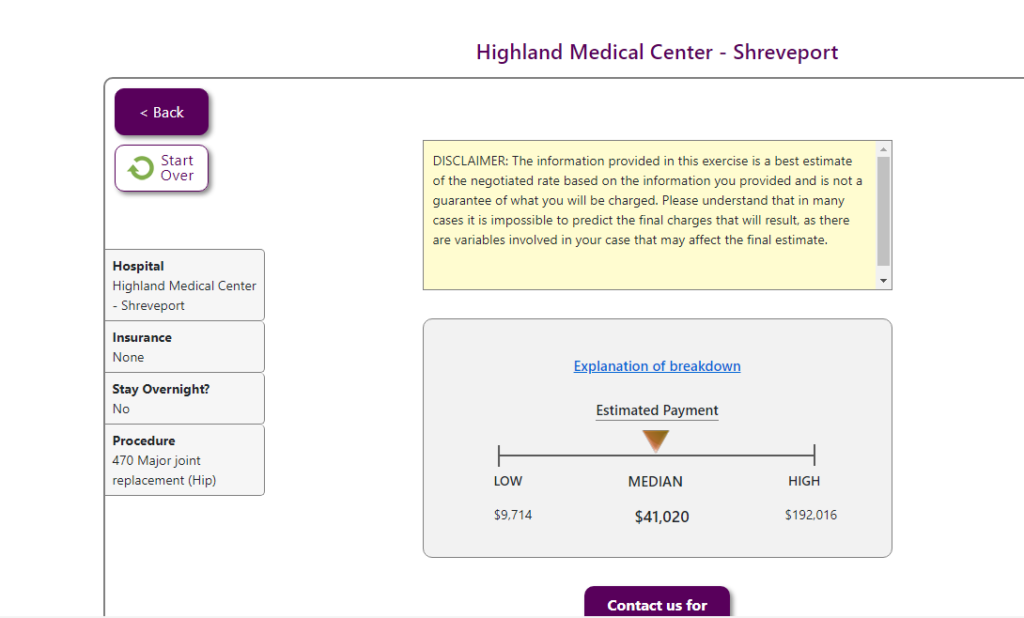

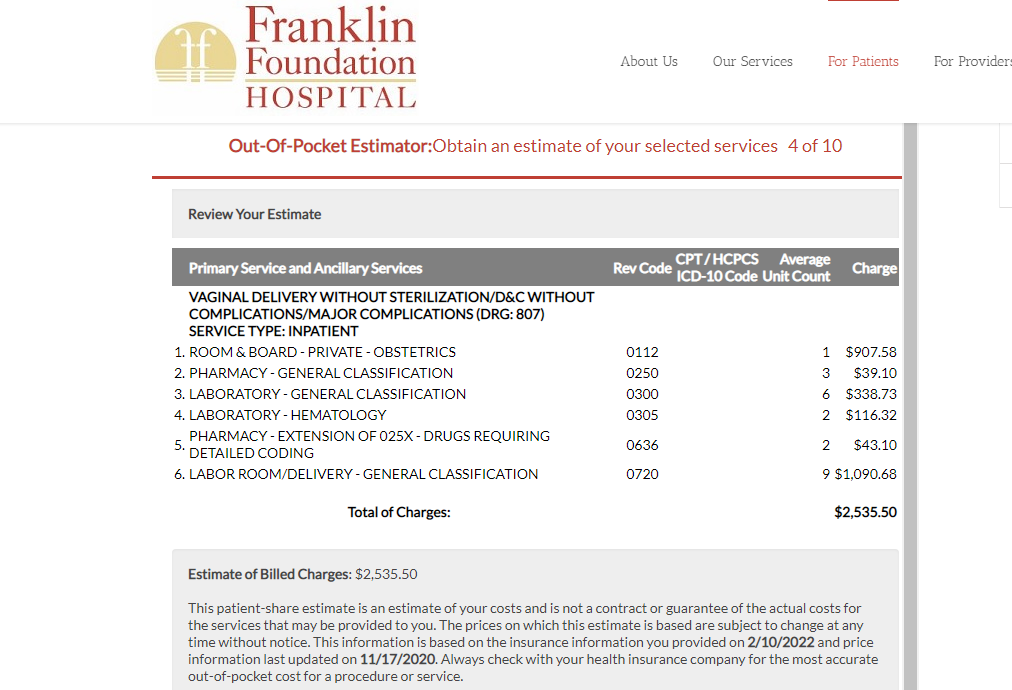

- Patients are still in the dark about their estimated costs. Transparency on procedure costs for patients remains low. A minority of hospitals in Arkansas (33%), Louisiana (42%), and Texas (30%) have truly accessible price estimation tools. And among those that do have accessible tools, the range of the estimates can vary so widely as to make them useless.

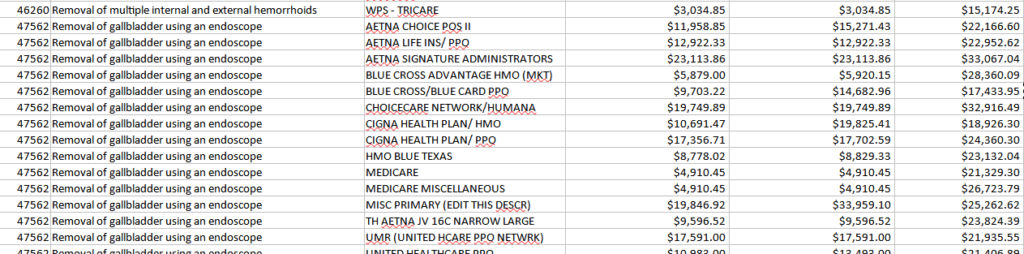

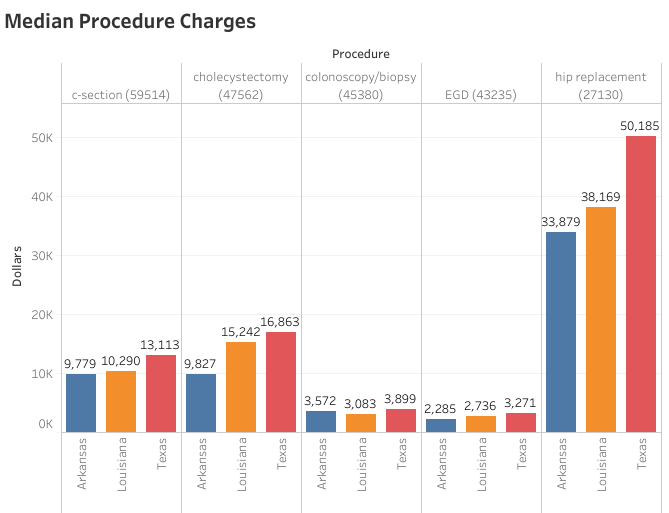

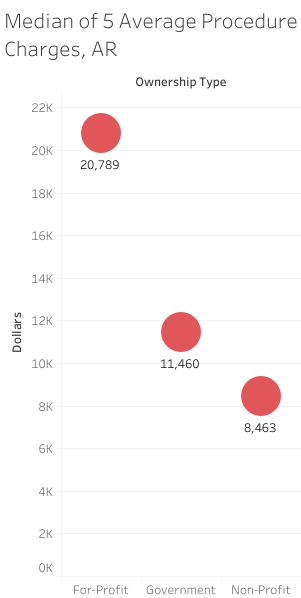

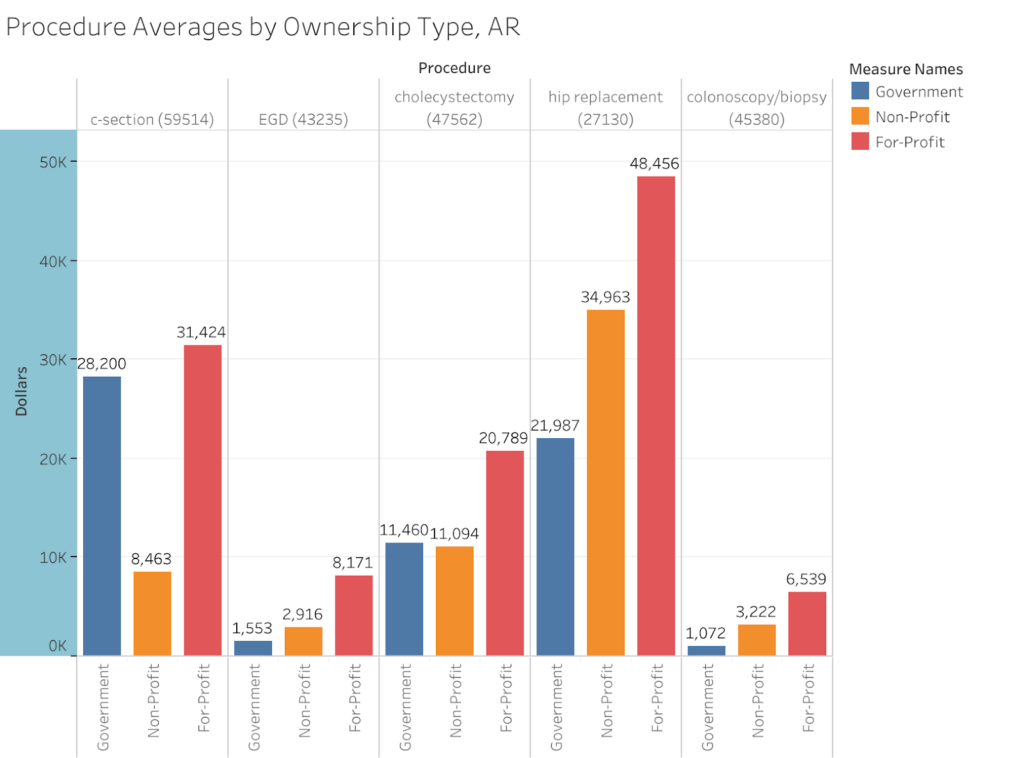

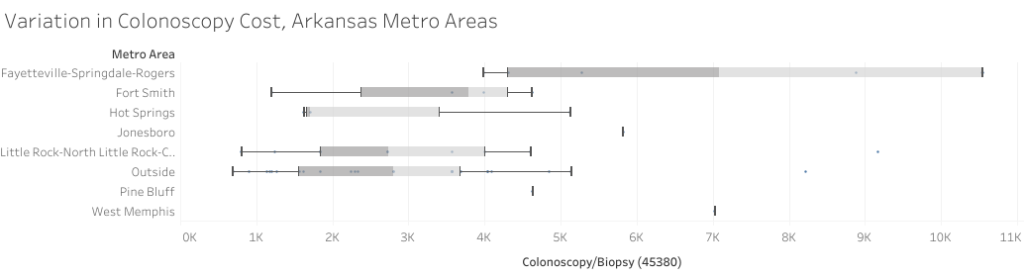

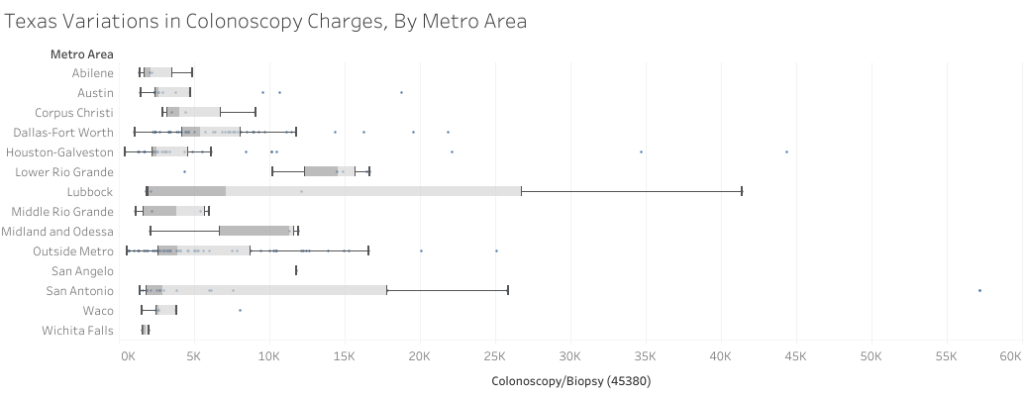

- Charges hospitals set are all over the place. There is massive variation in the charges set for procedures between and within all groupings of hospitals.

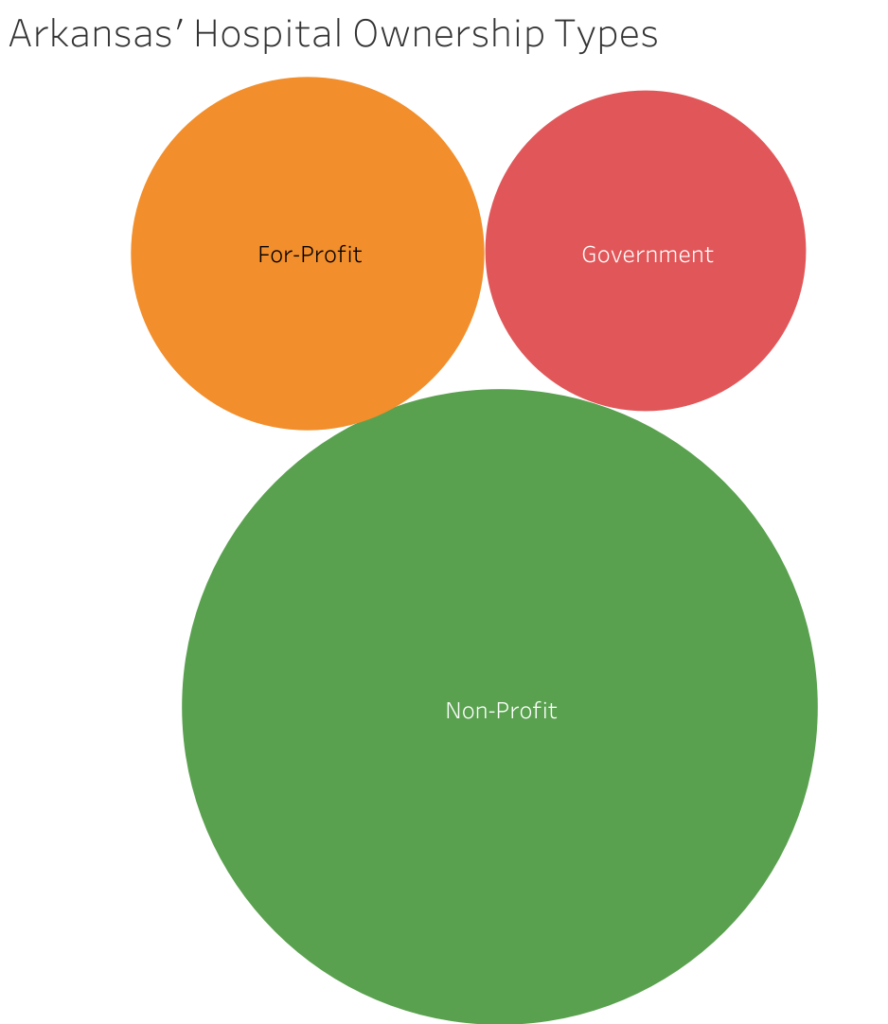

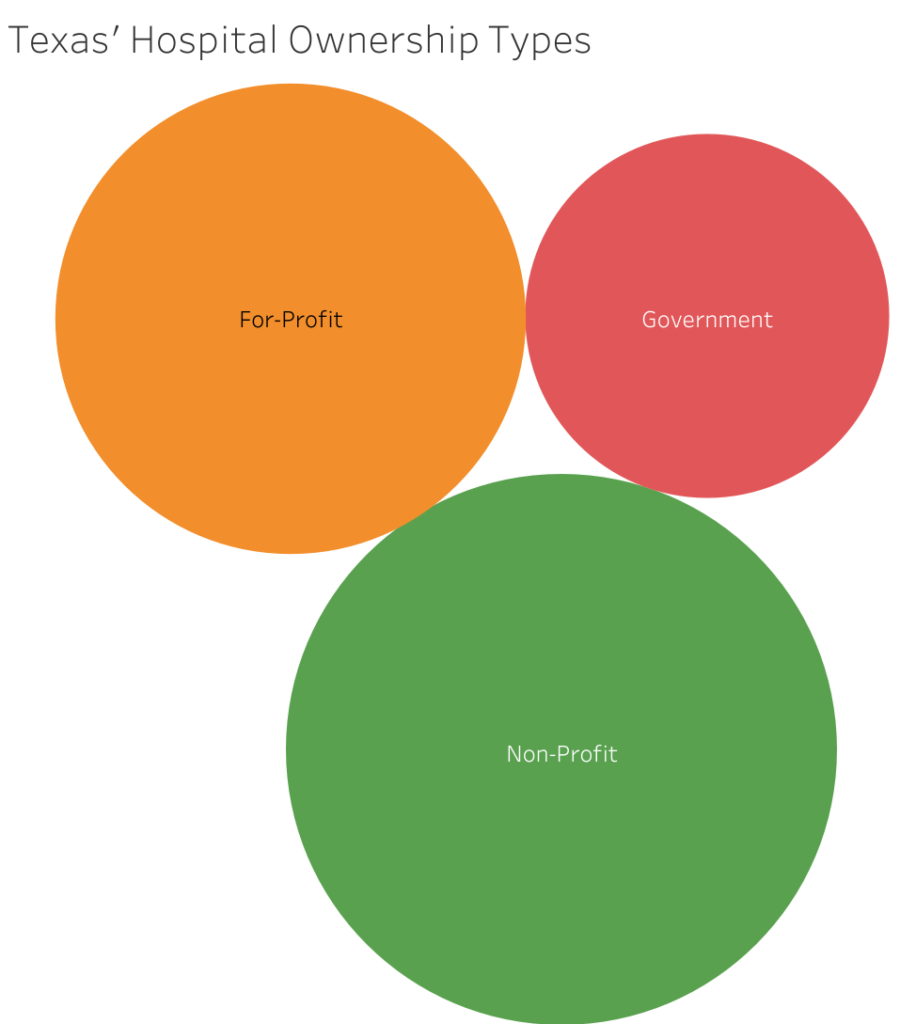

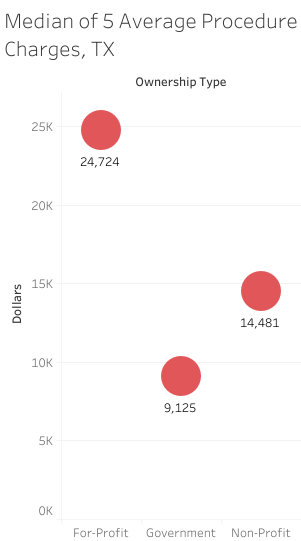

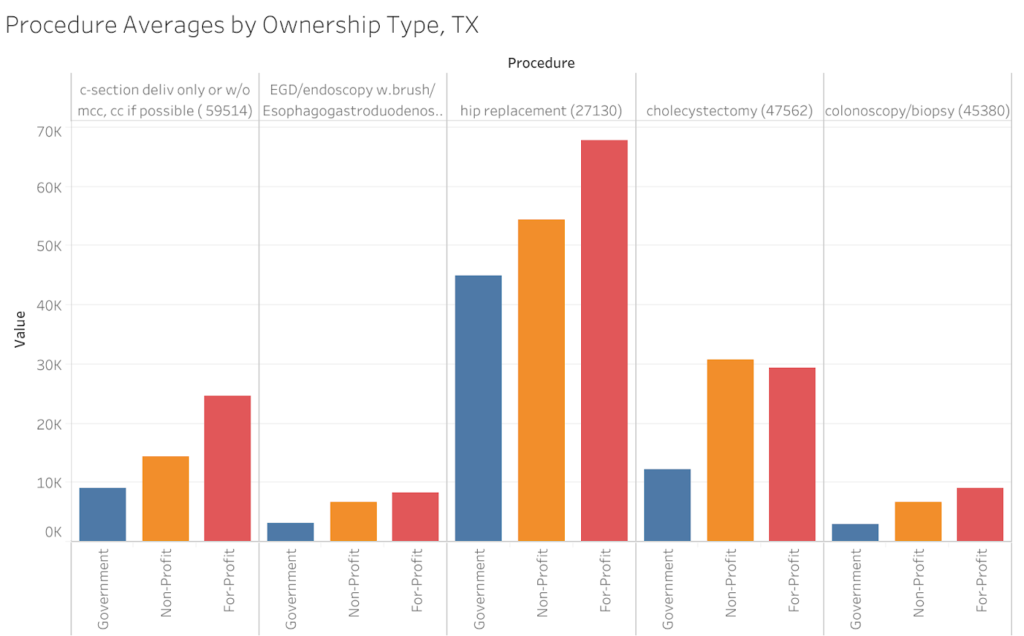

- For-profit hospitals set their charges higher than non-profits and government hospitals in Texas and Arkansas, but in Louisiana non-profits’ charges are much closer to for-profits.

- Texas hospitals set the highest charges of the three states, followed by Louisiana and then Arkansas.

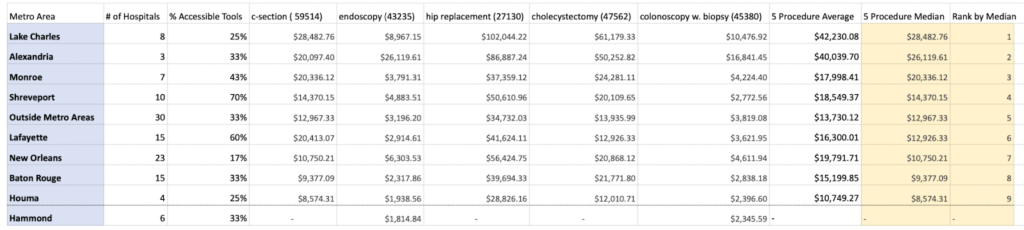

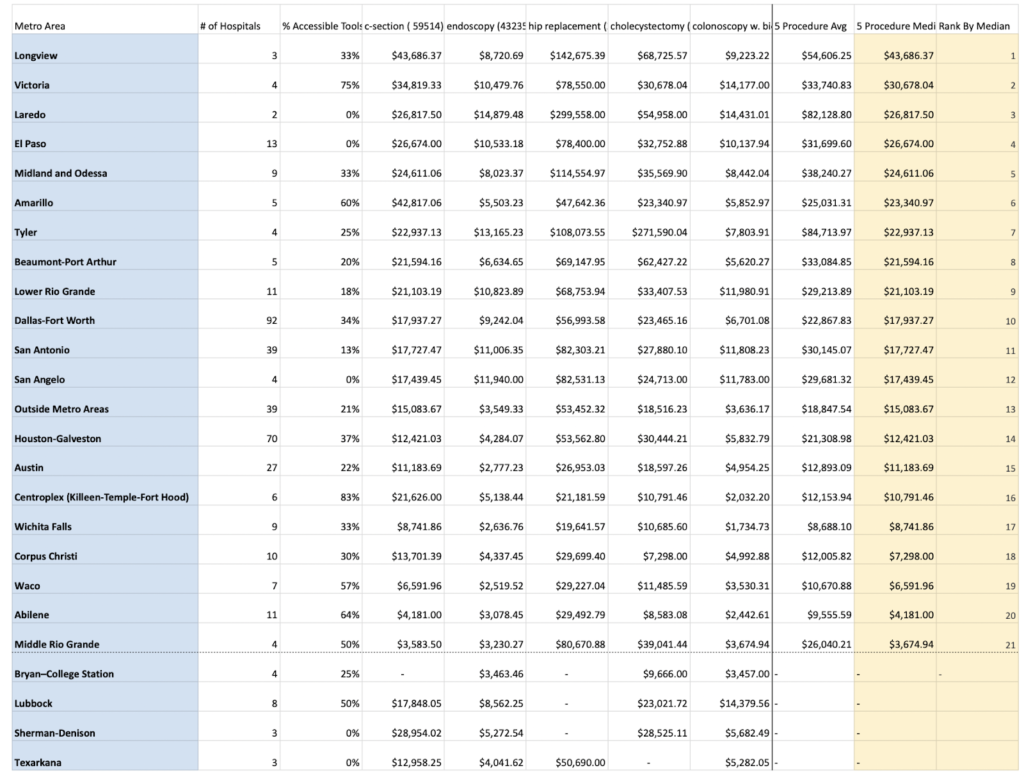

- The metro areas with the highest list prices in each state are Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers (Arkansas), Lake Charles (Louisiana), and Longview (Texas).

- ACORN stands ready to help researchers and patients in these three states get better understandings of the costs of care.

It’s so convoluted right now that … nobody can do a comparison across hospitals because every hospital is reporting differently. –Anonymous health industry executive

Introduction

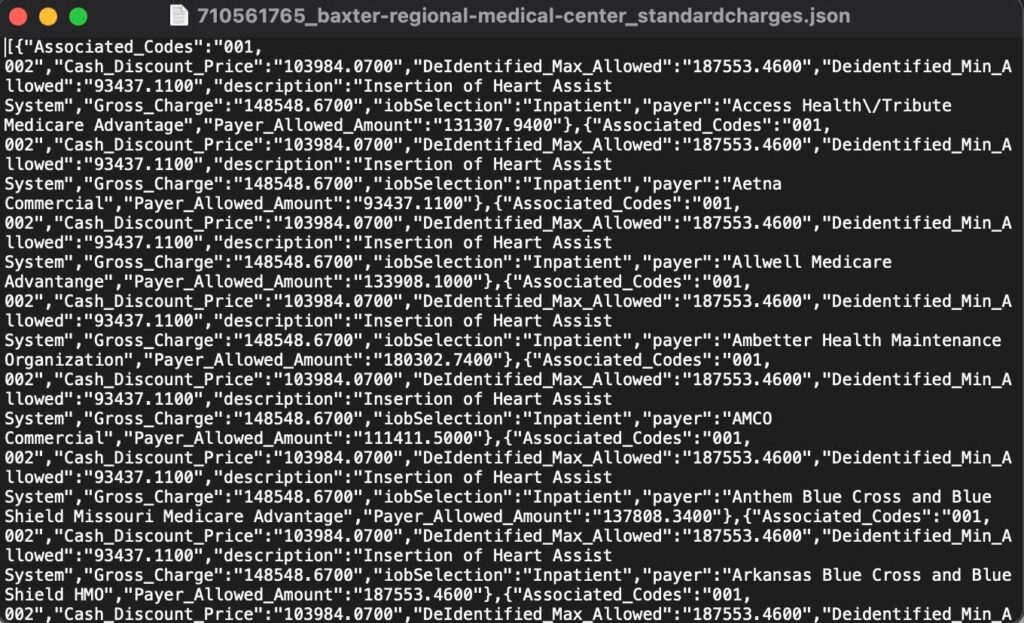

As of January 1, 2021, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began requiring most American hospitals disclose information about the prices of their services on their websites. Hospitals have since produced an ocean of new data to comply with this rule. In Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, where we studied this data, we found it to be incomplete, totally lacking in uniform standards, and riddled with inaccuracies. Varieties in hospitals’ methods for setting charges, and varieties in how they report those charges, mean that apples to apples comparisons are difficult. Nevertheless, given the dearth of studies seeking to use this new information to draw conclusions about trends in healthcare, we endeavored to wade through it and report our findings. While apple to apple comparisons might not be possible given the current landscape, we believe we have identified real trends at the “bushel” level. Indeed, we hope that our study will help prompt government and/or industry action to produce new and more uniform information–information that is actually useful to the patients they serve. Our study of hospitals’ data in Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, shows that the price transparency regulation falls far short of its stated goal of shedding light on healthcare costs for the following key, rectifiable reasons:- The regulation is inadequate in scope: Healthcare costs are not determined by providers alone, but via a process of negotiation between healthcare providers and payers–private and public (Medicare and Medicaid) insurances. Because the regulation does not require insurers to disclose information about their side of the deal, we are only seeing one side of the information we’d need to make reliable and specific estimates about the actual cost of care for patients.

- The regulation carries no significant penalties for noncompliance: Hospitals are frequently failing to comply in good faith with the spirit of the regulation–providing unnecessarily complex lists and inadequate tools if they provide them at all. The rare exceptions to this trend show us that good faith compliance is, in fact, attainable.

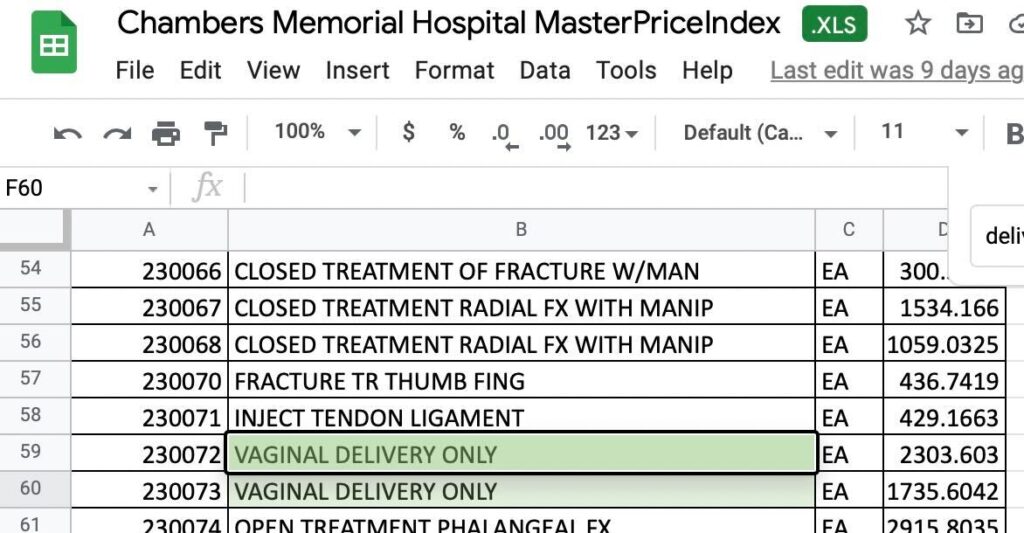

- The regulation itself fails to set standardized requirements for reporting, making direct and meaningful comparisons between hospitals inordinately difficult. The government’s failure to require the use of a standard coding system for procedures or require plain language descriptions of procedures has allowed this area to be yet another free-for-all in the American healthcare system, with as many variations in compliance as there are individual hospitals. The regulation should require plain language and move hospitals toward standardization of coding.

We found that price comparison tools were only truly accessible at 33% of Arkansas hospitals, 42% of Louisiana’s, and 30% of Texas’s. Of that minority whose tools were accessible, unfortunately, the estimates were often useless.

Background

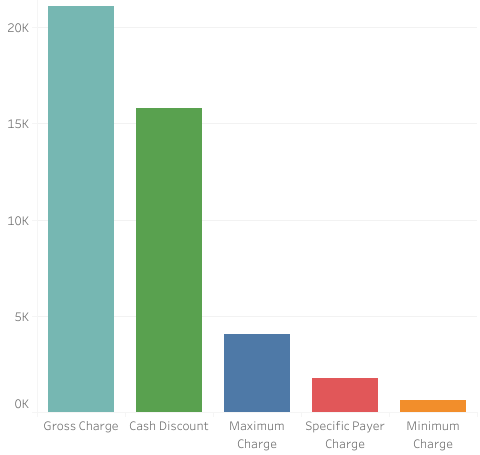

The government rationale for the price transparency rule is straightforward enough: healthcare costs continue to rise unabated, and requiring healthcare providers to disclose their prices to the public will help to bring down those costs by enabling comparison shopping. Think of it this way: If the only way you could purchase bread was by getting billed after eating it, and everyone got billed different amounts, bakers might be able to set all kinds of high prices for bread. Our ability to see the prices of breads before purchasing the one we want allows us to pick one that’s reasonably priced. The aggregate of those individual decisions (i.e., consumer demand) ought to interact with the aggregate of the bakers’ individual bread-making costs (i.e., supply) such that prices stabilize. Bread’s cost might fluctuate due to disruptions in bakers’ ability to supply it, but at least prices won’t grow year after year just because no one knows the price of the bread until after they eat it. In other words, hopefully, the idea is that “price transparency” would make health costs more like bread costs. However, healthcare is different from most goods and services in several fundamental ways. If healthcare is a commodity because we pay for it, then it is closer to commodities like funerals or repair services after a disaster than goods we buy in a store. The need for healthcare arises universally but unexpectedly, with costs generally beyond an individual’s ability to pay for them. Thus, people began pooling their resources, paying a bit into the pool at regular intervals in exchange for access to that pool in the moment of need–insurance, in other words. Prices, then, are not set so much by the relationship between the consumer and provider so much as the insurer and the provider. Insurers want to keep prices lower to minimize what they pay; providers want to get prices higher to maximize their profits. At the same time, the fact that services are insured make them more accessible than they would be if they all had to be paid for out of pocket, which pushes demand and prices up. In the United States, there is additional complexity: multiple insurers that compete with each other to pay multiple providers for healthcare costs. This is in contrast to a socialized healthcare system where the government is the main provider of service, as in the United Kingdom, or a single payer system where government insurance pays the costs to multiple providers, as in Canada. If everyone was in one insurance pool, the administrators of that pool would have more leverage with providers to keep prices lower. Consider that most hospitals simply cannot afford to turn down Medicare and Medicaid patients because there are just so many of them. The flip side is that hospitals have to then accept the government’s set rate of reimbursement and comply with CMS regulations, such as the price transparency rule. Recall private insurance companies’ fears during the Obamacare debate that a “public option” would end up out-competing private insurance, due in part to its ability to leverage a potentially massive pool of insured people. The complexity of endless negotiations between insurers and providers produces inefficiencies. Consider just one of the many Russian nesting dolls of problems unique to our system:[I]n efforts to negotiate better prices, insurers must be able to “threaten” to (and often do) exclude some clinicians or health care centers from their network. As a result, administrative dollars are spent to help find in-network clinicians or health care centers or steer patients to the lower-priced clinicians or health care centers in the network. Several industries have emerged to manage network and benefit complexity (e.g., firms that support patients as they navigate their network and their benefit design, as well as firms that support employers in designing benefits and choosing insurers). The associated administrative costs are spread across payers, clinicians and health care centers, employers, and even patients.1Little wonder that administrative costs make up an estimated 34% of American healthcare costs, as opposed to 17% of Canada’s2. In fact, the number of jobs supplied by the healthcare administration is itself a significant political barrier to efforts to reform and simplify healthcare delivery. The ballooning cost of healthcare is a long-term problem, but politicians are loath to make reforms that would lead to immediate job losses in its administration3. The upshot is, healthcare prices are extremely complex and varied not just because they aren’t transparent, but due to the basic market set-up of our healthcare system. The price transparency rule aims to start shining a light on this complexity–a flashlight lighting up thick layers of cobwebs. The rule itself has two main parts. One, hospitals have to provide systematic lists of all their prices in formats that can be processed by a computer (“machine readable files”). Hospitals often refer to this list as a “chargemaster” or list of standard prices. Two, they have to provide a “consumer friendly” list of the kind of common procedures a person could theoretically shop for in advance (“shoppable services”). But a hospital doesn’t set just one price for each procedure. It negotiates a different price with each individual insurer and sets another price for people paying directly without insurance (the “cash discount” or “self-pay” rate). All of this is separate from the rates government insurance pays hospitals for a procedure. So, the CMS regulation requires hospitals to publish the following four prices for each procedure in their systematic lists:

- What the hospital sets as its initial “charge,” list price, or gross cost. Think of this more as the hospitals’ starting point for their negotiations with insurers.

- The highest rate the hospital has negotiated with a given insurer for a given procedure. They don’t have to identify which insurer this is (thus, a “de-identified maximum”).

- The lowest rate the hospital has negotiated with an insurer (“de-identified minimum”) for a procedure.

- The ‘cash discount’ price hospitals charge people without insurance or people who ‘self-pay’.

- gross: $42,608.45

- min negotiated: $2,650.54

- payer specific negotiated: $10,450.28

- maximum negotiated: $10,450.28

- cash price: $19,173.80

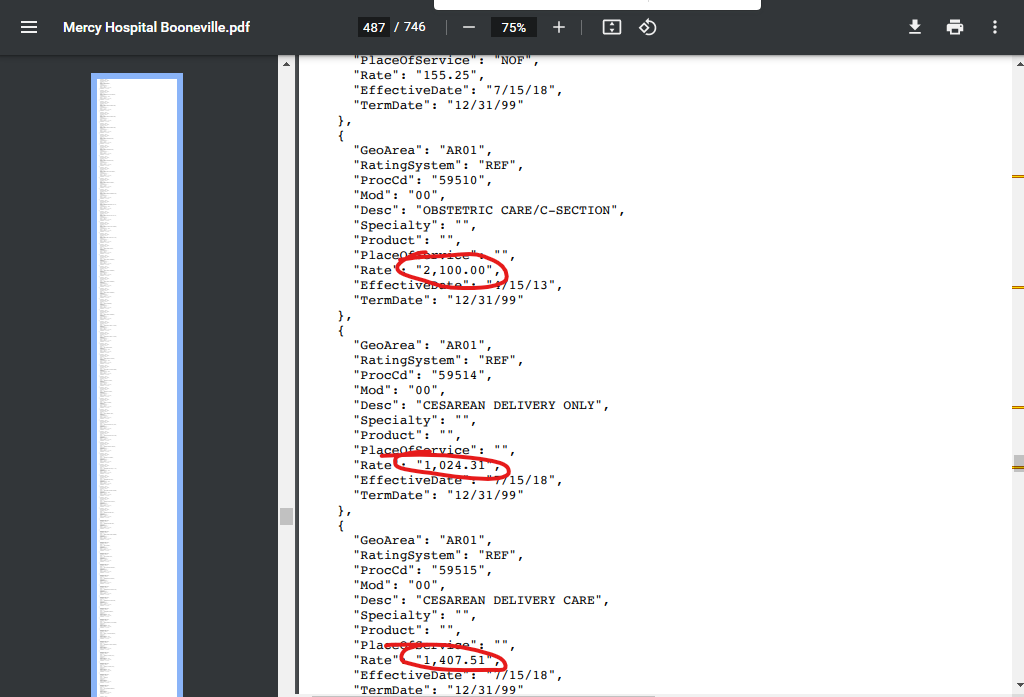

[T]he complex system of billing and coding that underlies bills…with its lines of alphanumeric codes and arcane medical abbreviations, has given birth to a gigantic new industry of consultants, armies of back-room experts whom medical providers and insurance companies deploy against each other in an endless war over which medical procedures were undertaken and how much to pay for them… Toward the end of the 20th century and into the next, as strategic coding increased, a new industry thrived. For-profit colleges offered medical-coding degrees, and internships soon followed. Because alphanumeric coding languages are as distinct from one another as Chinese is from Russian, different degree tracks are necessary, along with distinct professional organizations that offer their own particular professional exams, certifications and licensing. Hospital systems and insurers — which have become huge, Hydra-like enterprises — now all employ roomfuls of coding-program graduates to perform these tasks. Membership in the American Academy of Professional Coders has risen to more than 170,000 today from roughly 70,000 in 2008.Consider a usage of the most common coding system, the American Medical Association’s proprietary Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) system, at Mercy Hospital Boonville in Arkansas. It delineates separate or different charges for “obstetric care/c-section” (code 59510, $2,100), “cesarean delivery only” (code 59514, $1,024.31), and “cesarean delivery care” (code 59515, $1,407.51):

Methodology

As a New York Times’ investigation of hospital price transparency data put it, “hospital and insurers didn’t want you to see these prices,”8 let alone compare them. Perhaps it’s for this reason that there are studies of the range of costs for procedures9, but fewer comparing the costs between different sets of hospitals. Nevertheless, we refused to let complexity of the industry’s making deter us from analyzing trends in the industry, even if that complexity makes our measurement tool blunt and imperfect. Greater uniformity in charge reporting, whether undertaken due to industry or government pressure, will lead to greater accuracy. So, we built lists of hospitals in Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas, starting from state lists provided by the American Hospital Directory. We added additional campuses or sites and removed closed or inactive hospitals as we searched for each hospital’s website. We followed the Directory’s categorizations of these hospitals’ “ownership types” — that is, whether they are owned by a non-profit corporation, a corporation organized to provide returns to shareholders (including physicians), or overseen by a governmental authority. From those lists, we began to track who was compliant with the CMS rule. When they weren’t, we filed complaints with CMS–178 complaints across our three target states10. Then, we went back and located files from newly compliant hospitals and began analyzing all available lists of standard prices in the three states– 86 hospitals in Arkansas (70% now provide some kind of machine-readable file), 121 in Louisiana (77% have a machine-readable file), and 392 in Texas (90%). We have compiled each of these files into a central location and are providing them to the public to expedite additional research and comparison shopping. From an initial list of 30 common procedures that we collected data for, over time we settled on five that were relatively uncomplicated in their coding, appeared in many hospitals’ data, and which we felt confident could be compared across hospitals: a cesarean section, an upper GI-endoscopy (EGD/esophagogastroduodenoscopy with brush wash), hip replacement (arthroplasty), laparoscopic gallbladder removal (cholecystectomy), and colonoscopy with biopsy. We aimed, whenever possible, to choose the charges for the versions of these procedures without complications. The array of prices for every procedure at every hospital made arriving at a consistent variable difficult to compare and contrast difficult. Our researchers several times found that after having collected a ream of data on what we felt was reasonable to compare, a new piece of information showed us that it was not. For instance, we ended up not using our appendectomy price lists to make comparisons because we found major price variation between two methods of appendectomy, methods which were sometimes but not always specified by the hospital. However, we took nearly every hospital’s admonishment that costs could always be higher than the estimate as helpful methodological advice. Whenever the hospital listed only one price–the list/standard/gross charge–we used that. But, for instance, at Christus Shreveport, the gross charges listed by the hospital for a hip/knee replacement are $91,169.90, The hospital managed to fetch a higher rate from at least one insurance company so its “de-identified maximum” for the same procedure is $164,815.60. In this as in other cases, we took the higher of the two prices. Meanwhile, at Children’s Hospital New Orleans, the price of the same procedure has a gross of $251,182.00 while the de-identified maximum is lower–which is more typical– at $195,921.96. Again, we used the higher of the two listings. Therefore, while pinpointing the cost of the procedure at either hospital is impossible, it is reasonably certain that it would cost a person more at Children’s Hospital than it would at Christus Shreveport. For our analysis of the accessibility of the comparison price tools, our team divided them into four different categories: accessible, difficult to access, unavailable, or unreliable. “Unreliable” tools were those that didn’t give us price estimates for procedures we knew were available at the hospital, usually because they were listed in the chargemaster. For instance, Byrd Regional Hospital in Leesville, Louisiana proudly lists its full spectrum of maternity care offerings, but its price comparison tool says the hospital does not provide deliveries.

Analysis

We found median charges for our test procedures to be highest in Texas, followed by Louisiana, with Arkansas the lowest of the three. The average of medians for Louisiana’s charges was 17.2% higher than Arkansas’s; the average of medians for Texas’s charges was 47.2% higher than Arkansas’s.

Arkansas

Louisiana

Texas

Acknowledgements

A team of dedicated researchers made this report possible: Ryann Cohen, Rebecca Srour, Meagan Lee, Alison Hurwitz, Yuan Yueyue, Amanda Castillo, Ana Bergmann, Gracie Scott, Emma Sciarrone, Amelia Nugent, Isabelle Varone, Anna Washburn, Orion Howard, Gabby Chavez, Pooja Patel, Setah Alavia, Trey Gray, Emily Thompson, Julia Stern, Kelsey Liebman, and Khayin Maheia. David Thompson is research coordinator for the family of organizations that assembled this report, ACORN International, Labor Neighbor Research & Training Center, and Local 100 United Labor Unions. The full report and the data set is available at www.acorninternational.org and the websites of the partner organizations. Questions on the report or more information can be obtained by email from David Thompson research@chieforganizer.org or from Wade Rathke chieforganizer@acorninternational.org who initiated the report as part of a series of similar reports published in Social Policy on the failure of hospitals to provide charity care as required by the Affordable Care Act and the more recent report in Social Policy 51.4 on non-compliance with this CMS reporting requirement.Take Action and Follow-Up

If you need help making it through the maze that we have described, contact us at www.acorninternational.org, www.laborneighbor.org, or www.unitedlaborunions.org for assistance!1 Chernew, Michael and Harrison Mintz, “Administrative Expenses in the US Health Care System: Why So High?” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2785479 2 Himmelstein, Campbell, Woolhandler, “Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada,” Annals of Internal Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31905376/ 3 https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2016/07/what-is-the-effect-of-obamacare-economy-000164/ 4 See, e.g., Louisiana’s Lake Charles Memorial Hospital’s chargemaster, which lists some 52 prices for spinal fusion, or Madison Parish Hospital in Tallulah, Louisiana which lists just one. 5https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/29/magazine/those-indecipherable-medical-bills-theyre-one-reason-health-care-costs-so-much.html 6 https://www.cms.gov/files/document/steps-machine-readable-file.pdf 7 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdX3Kny6lLk 8 Kliff, Sarah and Josh Katz, “Hospitals and Insurers Didn’t Want You To See These Prices. Here’s Why,” August 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/08/22/upshot/hospital-prices.html 9 For instance, this excellent study shows how wildly prices can vary for the same procedure in certain metro areas: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/price-transparency-and-variation-in-u-s-health-services/ 10 https://acorninternational.org/index.php/2021/11/30/complaints-filed-178-hospitals-fail-to-provide-federally-mandated-price-transperency/